My goal is to differentiate which of the brain changes in people with major psychiatric disorders are primary, i.e. associated with genetic risk and which are secondary, i.e. related to the presence of the illness, comorbid conditions or treatment. Whereas the primary changes could aid in early diagnosis, the secondary changes may perhaps be prevented. To this goal we have run a range of projects, including:

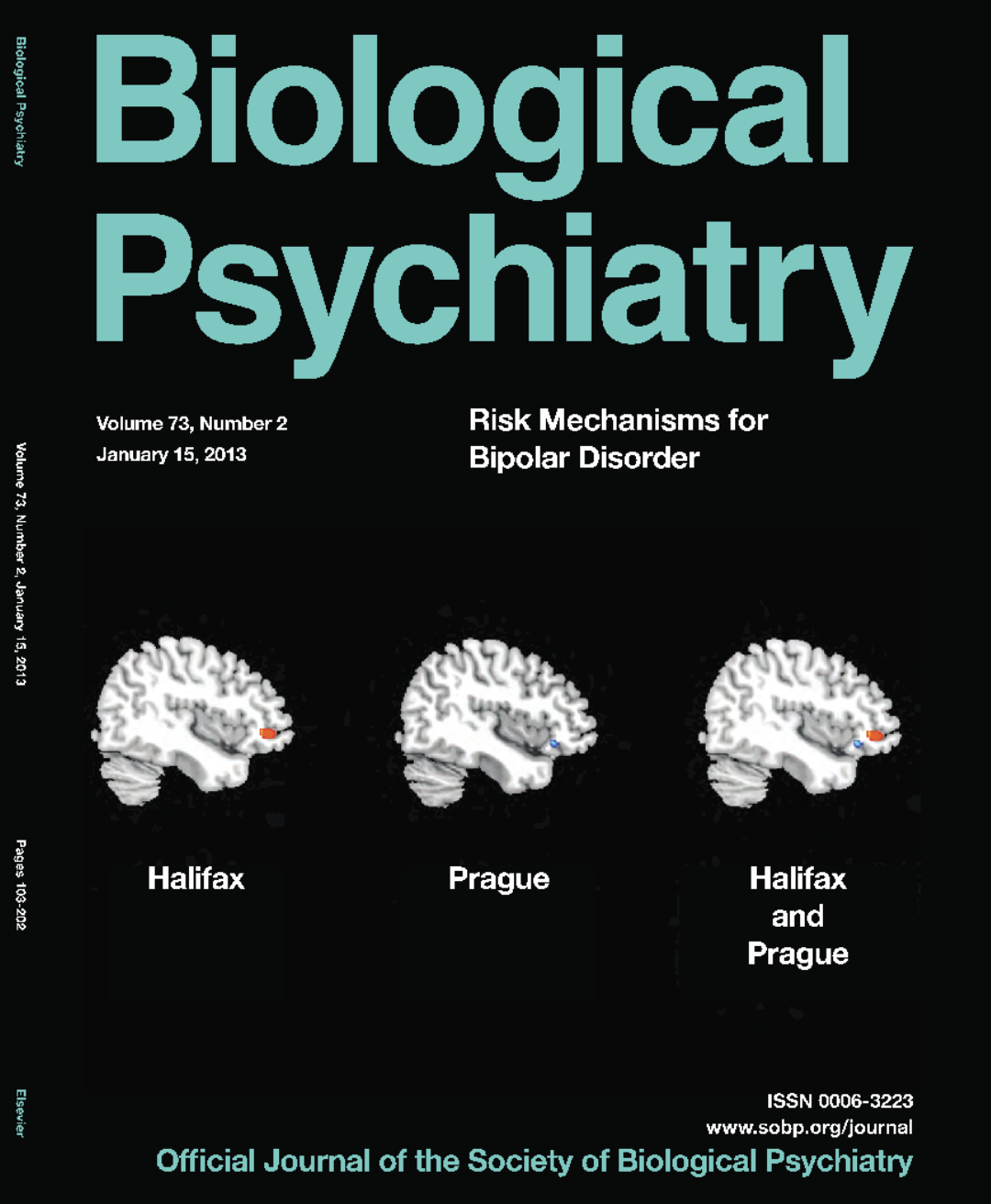

Genetic High Risk Studies

One of the best ways to identify biological risk factors for bipolar disorders (BD) is to study offspring of parents with BD. This is called genetic high-risk design. By focusing on unaffected relatives of BD patients, we eliminate the effects of illness or psychiatric medications, which could confound the results. We were among the first to perform genetic high-risk neuroimaging studies. These studies provided replicated evidence that larger right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) volume was a marker of genetic risk for BD – (featured on the cover page of Biological Psychiatry). Our IFG findings have since been replicated by 4 other independent groups. In a related study, we provided proof of concept that applying machine learning (ML) to structural brain imaging could help identify subjects at genetic risk for BD, in part based on the larger rIFG. In one of the first differential diagnostic brain imaging studies, we showed that advanced brain age was present early in the course of schizophrenia, but not early in the course of BD. In addition, we documented that many of the neuroimaging changes previously reported in BD are absent in those at risk for the illness. This was replicated in a number of subsequent studies, including the largest such investigation by the ENIGMA.

Diagnostic Use of Brain Imaging in Psychiatry

Unfortunately, MRI of the brain has limited use in everyday clinical practice of psychiatry. This is likely related to heterogeneity, where many of the brain changes in severe mental illness (SMI) may reflect other things than just the diagnosis, i.e. comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions, effects of medications, effects of episodes of illness, etc. It is also related to the fact that the traditional mass-univariate methods of data analyses do not respect the brain network characteristics of the disorders. We have been trying to understand the non-diagnostic factors which contribute to brain alterations in SMI, including comorbidities, treatments and episodes of illness. We have been testing multivariate techniques to analyze the brain imaging data. I was the project lead of the largest machine learning diagnostic brain imaging study in BD, including 3020 participants from the ENIGMA consortium (Nunes et al. Molecular Psychiatry, 2018), which was listed among the 10 most significant research contributions of the year by Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF). We have also been using clustering and principal component analysis to better understand how patterns of brain alterations link with clinical and demographic characteristics. We were one of the early adopters of normative modelling, specifically machine learning based brain age estimation, which provides an intuitive, summary measure of whole brain structure and can be used to monitor impact of specific risk or protective factors on the brain.

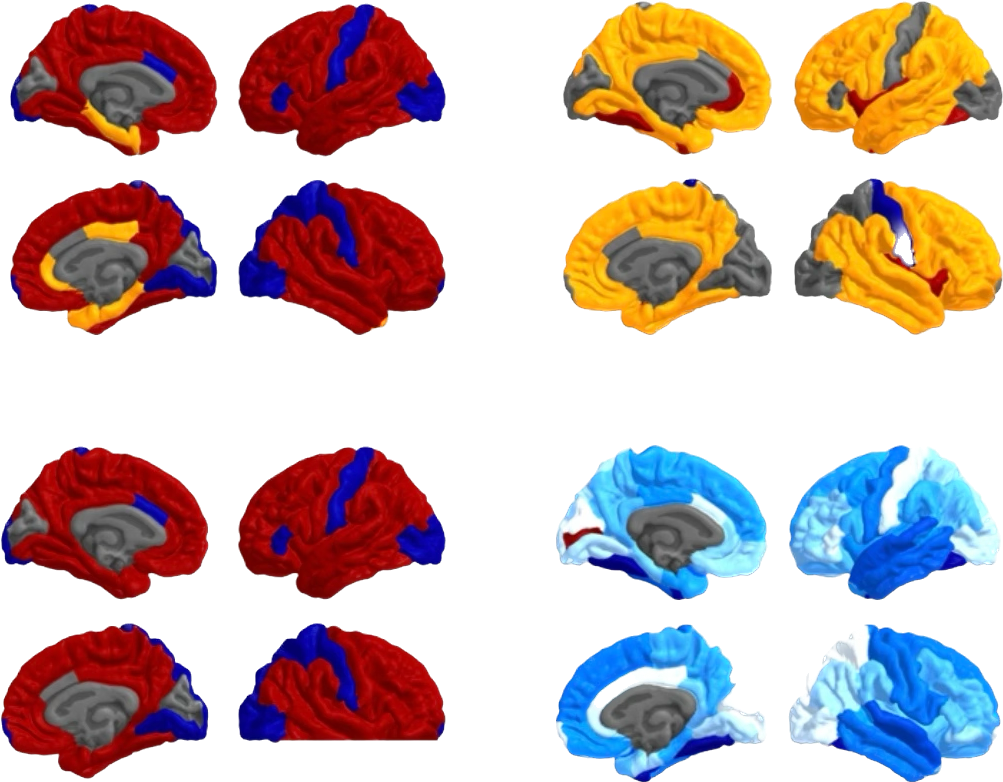

Obesity and Brain Structure in People with SMI

Obesity is disproportionately frequent in people with SMI, such as major depression, bipolar disorders and schizophrenia. The brain is one of the target organs for both obesity and SMI. Yet, very few studies have investigated the impact of obesity on the brain in SMI. To this goal, we established the BMIX working group within the ENIGMA consortium. We also performed dedicated studies in BD and first episode psychosis investigating the interplay between SMI, obesity, and brain alterations. We demonstrated for the first time the associations between: 1) obesity and neurostructural, neurochemical brain changes in BD, 2) obesitogenic medications, i.e. atypical antipsychotics and higher brain age, 3) obesity and lower regional brain volumes and higher brain age in first episode psychosis (FEP). In a study including 2735 individuals, we demonstrated that some of the most replicated brain alterations in BD, including larger ventricles, were to a large extent (up to 47%) mediated by obesity,and that both BD and schizophrenia were associated with similar cortical alterations as obesity. In a prospective study, we showed that higher baseline body mass index (BMI) predicted acceleration of brain aging in the next 1-2 years. Specifically, for every one-point increase in BMI, the annual rate of brain ageing increased by approximately an additional month. To raise awareness of these concerning findings, we co-edited a special thematic issue Brain-Metabolic Crossroads in Severe Mental Disorders – Focus on Metabolic Syndrome, with contributions from 87 authors from around the world and >44400 views.

Risk Factors for Brain Alterations in BD

Many of the brain alterations that we see in people with diagnosed BD are not found in people at risk for the disorder. Therefore, these brain changes need to develop only after the onset of illness and perhaps we can prevent them. To do this, we need to identify specific risk factors for brain alterations in SMI. We were the first to demonstrate that type 2 diabetes mellitus or insulin resistance were associated with brain alterations in BD (Biological Psychiatry, Neuropsychopharmacology), that BD complicated by diabetes presents with adverse psychiatric sequelae, and that the clinical and brain imaging outcomes may be linked (British Journal of Psychiatry, Bipolar Disorders, etc).

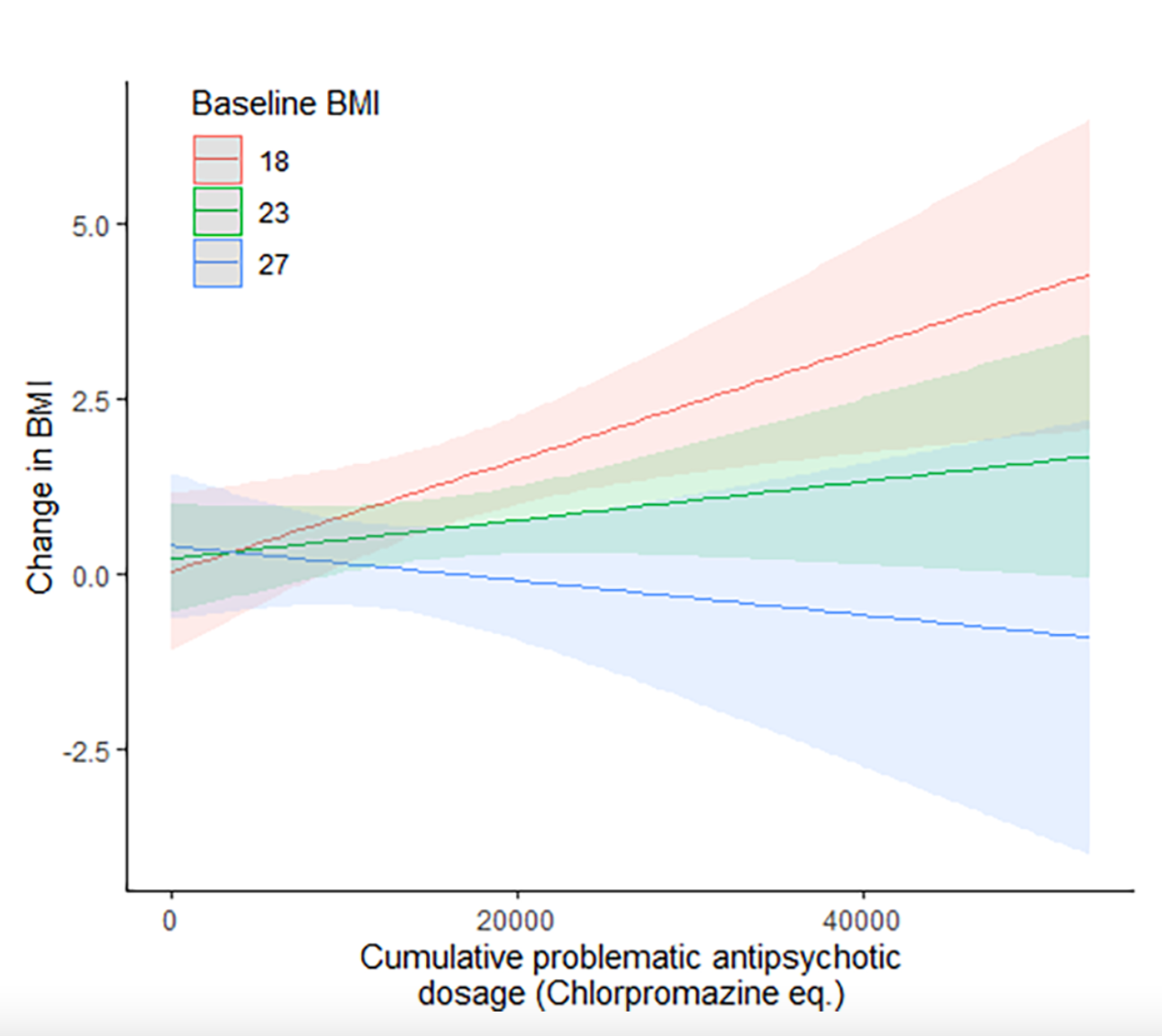

Obesitogenic Effects of Medications

The brain imaging studies have sparked our interest in better understanding the obesitogenic effects of psychiatric medications. In a unique study we tracked daily exposure to medications in people during the first hospitalization for psychosis and linked it to changes in weight and metabolic markers. This study revealed that low to normal baseline weight was the strongest predictor of weight gain on antipsychotic medications. The weight gain in these people was clinically significant in almost half of them (45.9%) and resulted in early onset of metabolic abnormalities. We are now looking at better ways how to quantify the overall metabolic impact of medications over time.

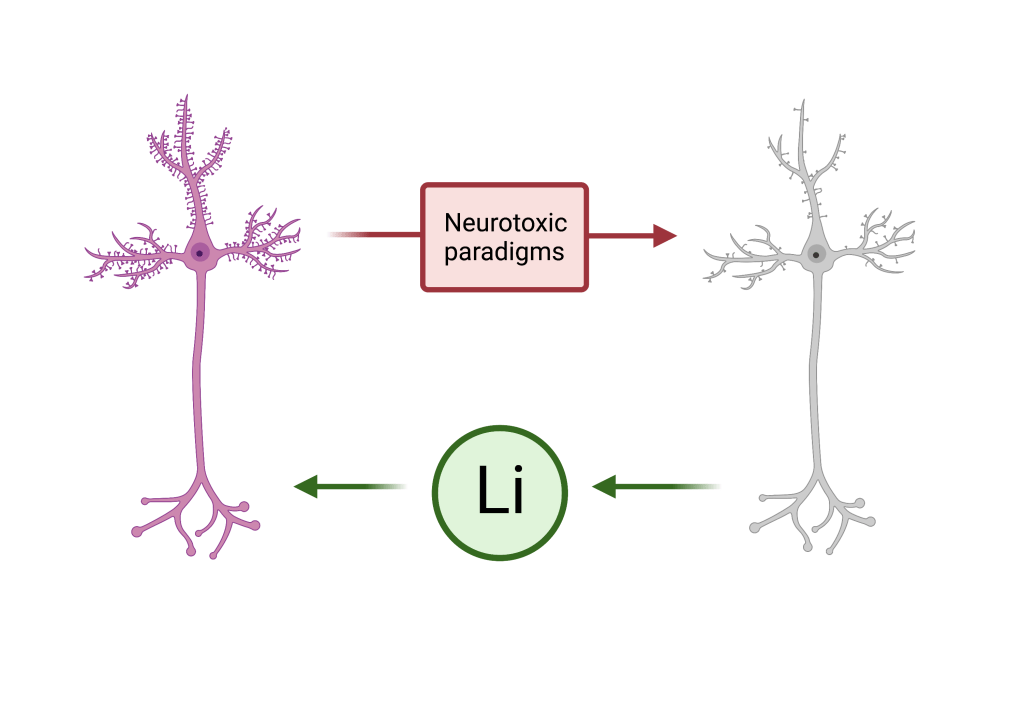

Neuroprotective Effects of Lithium

Hand in hand with identifying risk factors for brain alterations, we also need to understand factors which may protect the brain. In collaboration with IGSLi group, we ran a multi-site international study, which showed that the presence or absence of brain imaging alterations in BD was contingent on the presence or absence of Li treatment. These findings were replicated across participating sites and different brain imaging measures. Using machine learning, we also showed that bipolar disorders are associated with older looking brains, but not in people treated with Li. Interestingly, these studies also suggested that the positive association between long-term Li treatment and hippocampal volumes was independent of mood stabilizing treatment response and occurred even in participants with episodes of illness while on Li. Thus, a protective effect of lithium might be a result of its biological properties, not an artifact of treatment response. Consequently, these actions of Li on brain structure may not be restricted to those with bipolar disorders and could benefit participants with other neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzhiemer’s disease (AD). In collaboration with ophthalmology and collaborators in Brazil and Denmark we are investigating associations between Li treatment and risk for glaucoma (illness characterized by neurodegeneration in retina), using population databases and animal models of glaucoma.